「Existence」| 存在

13 (Sat) ~ 28 (Sun) April 2024 | 2024年4月13日(土)~28日(日)

Gallery G-77 presents an exhibition by Israeli photographers Anna Hayat and Slava Pirsky titled ‘Existence,’ as part of the program KG+ (festival Kyotographie 2024).

「ギャラリー G-77 は、プログラム KG+ (Kyotographie 2024) の一環として、イスラエル人写真家のアンナ・ハヤットとスラヴァ・ピルスキーによる展覧会「Existence」を開催します。

Israeli photographers Anna Hayat and Slava Pirsky craft their art using large-format black-and-white Polaroid photographs, taken within the studio and outside of it.

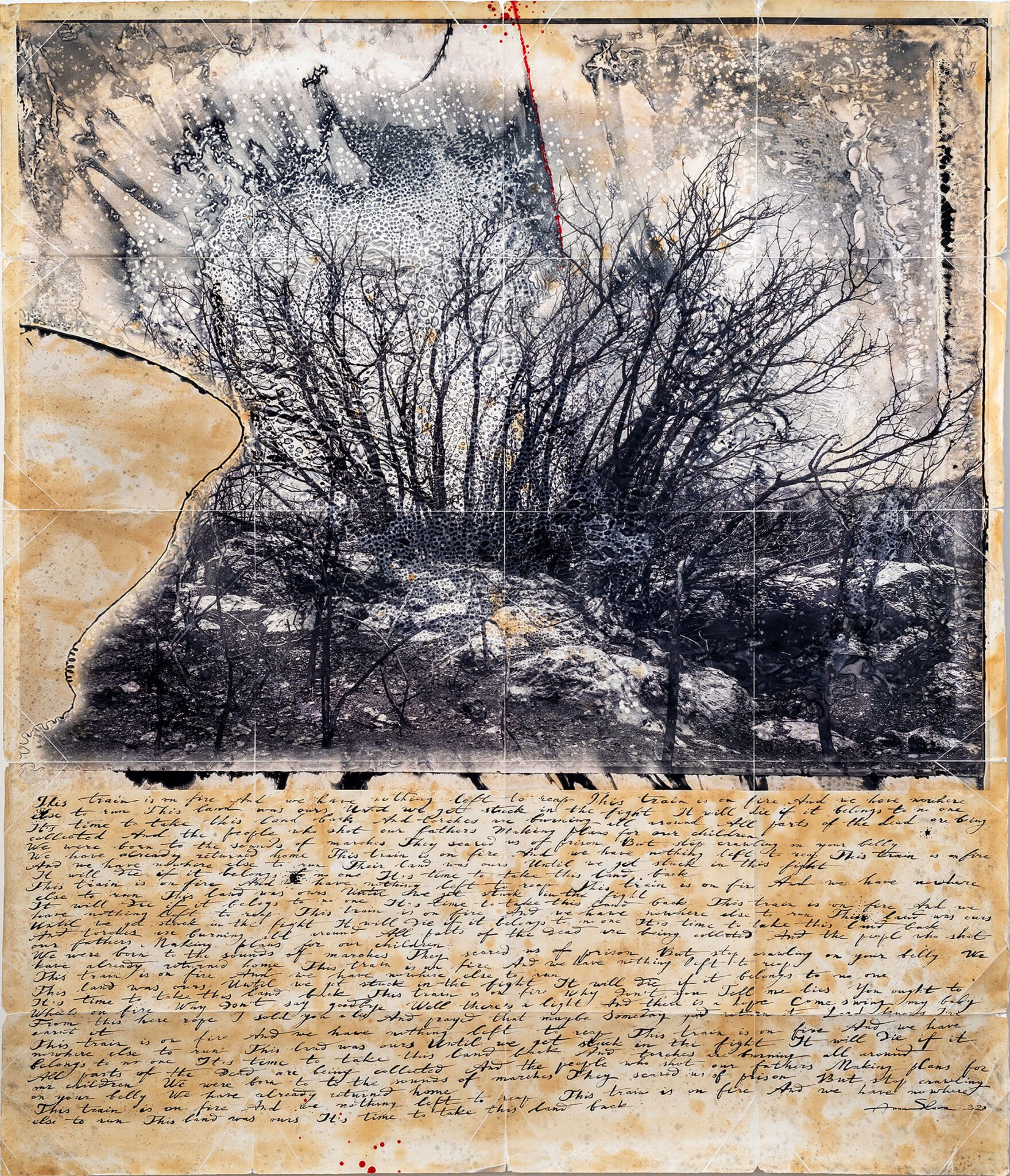

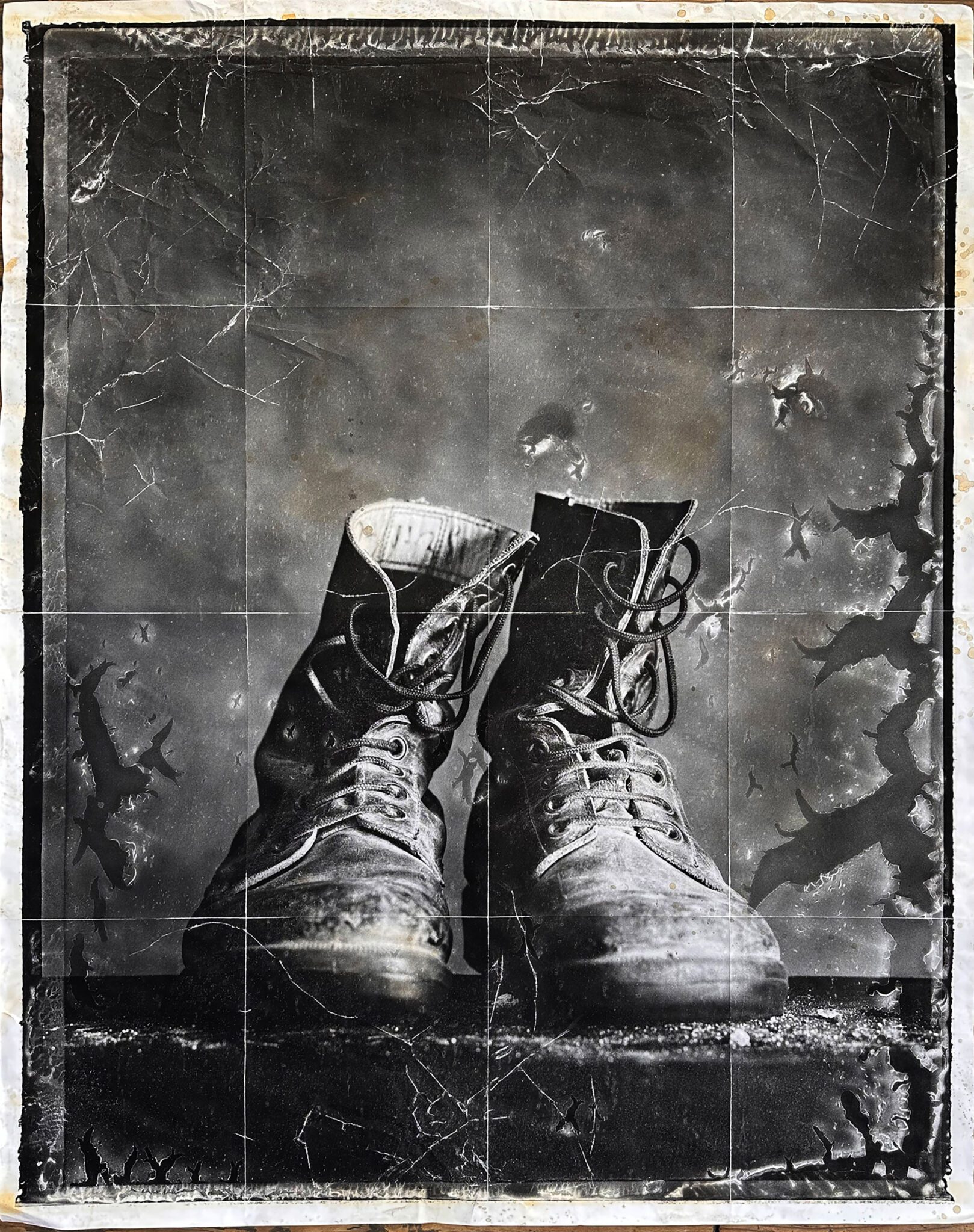

These works explore trauma, self-sacrifice, and the fragility of life. Through their lens, they explore facets of Israeli society intertwined with existential challenges, born out of omnipresence of war and terror. People, landscapes, flora, and objects all find their place in their compositions. Departing from strict documentary representation, the artists construct metaphorical imagery that resonates with current events.

Behind each work lies not only an emotional impulse but also a cultural narrative. Song lyrics, specific stories, poems – different contexts are weaved together into a unified image, carrying a multi-layered meaning. The message sealed in each work draws from various sources of art, everyday life, news and literature.

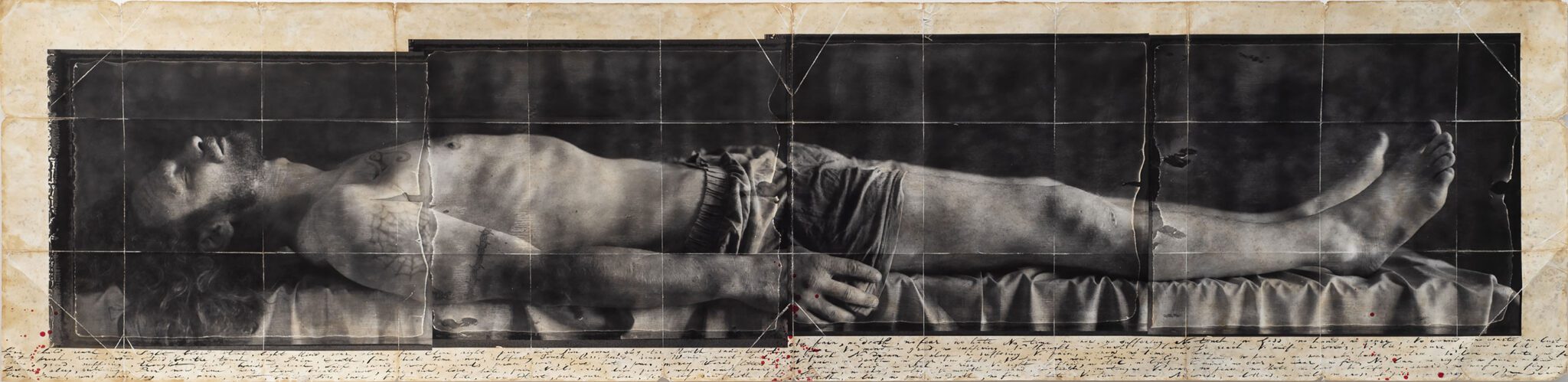

The exhibition features several works from different series, but they are all united by one style and theme. The main series in the exhibition is “My Personal Jesus,” which incorporates references to Renaissance masterpieces. In this series, the artists skillfully blend light, vivid, and detailed aesthetics of that era with modern photography. By inviting viewers to compare and analyze images of people and objects from great masters alongside their own, they provide an opportunity to perceive and interpret the essence of the presented artworks within the context of themes and ideas of the past.

In response to the October 7th terrorist attack and its aftermath, Hayat and Pirsky present new works that complement the exhibition with a more direct approach. Scenes such as the desolate café in the attacked kibbutz and shattered, mutilated dolls suspended in unnatural poses speak volumes about the tragedy. These pieces evoke feelings of pain and sorrow, captivating viewers’ attention and prompting empathy and deep contemplation.

Experimenting with materials and techniques, the artists create photographs that look as if they belong to a historical archive. Traces of folding on weathered paper, uneven edges, and the distinctive grayscale tones are intended to convey the influence of time. This visual effect enhances the impression, mystifying and intriguing the viewer, inviting them to believe that these photographs were created long ago, perhaps in a pre-photographic era, or that we are viewing them from a distant future. The works become artifacts of contemporary history.

アンナ・ハヤットとスラヴァ・ピルスキー “Existence”

イスラエルの写真家、アンナ・ハヤットとスラヴァ・ピルスキーは、スタジオ内外で撮影した大判の白黒ポラロイド写真を使って作品を制作しています。

これらの作品は、トラウマ、自己犠牲、人生の虚弱さを探求しています。 彼らはレンズを通して、戦争とテロの蔓延から生まれた実存的な課題と絡み合うイスラエル社会の諸相を探求します。 人物、風景、植物、オブジェクトなど、すべてが彼らの作品の構図の中にあります。厳密なドキュメンタリー表現から離れて、アーティストたちは現在の出来事に共鳴する比喩的なイメージを構築します。

それぞれの作品の背後には、感情的な衝動だけでなく、文化的な物語も存在します。 歌の歌詞、具体的なストーリー、詩など、さまざまな文脈がひとつのイメージに織り込まれ、多層的な意味を持ちます。 それぞれの作品に込められたメッセージは、芸術、日常生活、ニュース、文学など様々なソースから引き出されています。

この展覧会では、異なるシリーズからいくつかの作品が展示されていますが、それらはすべてひとつのスタイルとテーマで統一されています。 展覧会のメインシリーズは、ルネッサンスの名画を引用した「My Personal Jesus」です。 このシリーズでは、アーティストは当時の明るく鮮やかで緻密な美学と現代の写真を巧みに融合させています。 偉大な巨匠の人物や物のイメージと彼らのイメージを比較、分析してもらうことで、過去のテーマや思想の文脈の中で提示された作品の本質を認識し、解釈する機会を提供します。

10月7日のテロ攻撃とその余波を受けて、ハヤットとピルスキーは、より直接的なアプローチで展覧会を補完する新作を発表します。 襲撃されたキブツの荒涼としたカフェや、粉々に砕かれ、不自然なポーズで吊るされた人形などの光景が、この悲劇を雄弁に物語っています。 これらの作品は痛みや悲しみの感情を呼び起こし、見る人の注意を引きつけ、共感や深い思索を促します。

素材や技術を試しながら、アーティストたちはあたかも歴史的遺物のような写真を作成します。 風化した紙の折り跡、不均一なエッジ、独特のグレースケールの色調は、時間の影響を伝えることを意図しています。 この視覚効果は見る者の印象を高め、神秘的で興味をそそるものであり、これらの写真が遠い昔、おそらく写真以前の時代に制作されたもの、あるいは私たちがそれらを遠い未来から見ているかのような錯覚を誘います。 作品は現代史の遺物となります。

Israeli photographers Anna Hayat and Slava Pirsky craft their art using large-format black-and-white Polaroid photographs, taken within the studio and outside of it.

These works explore trauma, self-sacrifice, and the fragility of life. Through their lens, they explore facets of Israeli society intertwined with existential challenges, born out of omnipresence of war and terror. People, landscapes, flora, and objects all find their place in their compositions. Departing from strict documentary representation, the artists construct metaphorical imagery that resonates with current events.

Behind each work lies not only an emotional impulse but also a cultural narrative. Song lyrics, specific stories, poems – different contexts are weaved together into a unified image, carrying a multi-layered meaning. The message sealed in each work draws from various sources of art, everyday life, news and literature.

The exhibition features several works from different series, but they are all united by one style and theme. The main series in the exhibition is “My Personal Jesus,” which incorporates references to Renaissance masterpieces. In this series, the artists skillfully blend light, vivid, and detailed aesthetics of that era with modern photography. By inviting viewers to compare and analyze images of people and objects from great masters alongside their own, they provide an opportunity to perceive and interpret the essence of the presented artworks within the context of themes and ideas of the past.

In response to the October 7th terrorist attack and its aftermath, Hayat and Pirsky present new works that complement the exhibition with a more direct approach. Scenes such as the desolate café in the attacked kibbutz and shattered, mutilated dolls suspended in unnatural poses speak volumes about the tragedy. These pieces evoke feelings of pain and sorrow, captivating viewers’ attention and prompting empathy and deep contemplation.

Experimenting with materials and techniques, the artists create photographs that look as if they belong to a historical archive. Traces of folding on weathered paper, uneven edges, and the distinctive grayscale tones are intended to convey the influence of time. This visual effect enhances the impression, mystifying and intriguing the viewer, inviting them to believe that these photographs were created long ago, perhaps in a pre-photographic era, or that we are viewing them from a distant future. The works become artifacts of contemporary history.

アンナ・ハヤットとスラヴァ・ピルスキー “Existence”

イスラエルの写真家、アンナ・ハヤットとスラヴァ・ピルスキーは、スタジオ内外で撮影した大判の白黒ポラロイド写真を使って作品を制作しています。

これらの作品は、トラウマ、自己犠牲、人生の虚弱さを探求しています。 彼らはレンズを通して、戦争とテロの蔓延から生まれた実存的な課題と絡み合うイスラエル社会の諸相を探求します。 人物、風景、植物、オブジェクトなど、すべてが彼らの作品の構図の中にあります。厳密なドキュメンタリー表現から離れて、アーティストたちは現在の出来事に共鳴する比喩的なイメージを構築します。

それぞれの作品の背後には、感情的な衝動だけでなく、文化的な物語も存在します。 歌の歌詞、具体的なストーリー、詩など、さまざまな文脈がひとつのイメージに織り込まれ、多層的な意味を持ちます。 それぞれの作品に込められたメッセージは、芸術、日常生活、ニュース、文学など様々なソースから引き出されています。

この展覧会では、異なるシリーズからいくつかの作品が展示されていますが、それらはすべてひとつのスタイルとテーマで統一されています。 展覧会のメインシリーズは、ルネッサンスの名画を引用した「My Personal Jesus」です。 このシリーズでは、アーティストは当時の明るく鮮やかで緻密な美学と現代の写真を巧みに融合させています。 偉大な巨匠の人物や物のイメージと彼らのイメージを比較、分析してもらうことで、過去のテーマや思想の文脈の中で提示された作品の本質を認識し、解釈する機会を提供します。

10月7日のテロ攻撃とその余波を受けて、ハヤットとピルスキーは、より直接的なアプローチで展覧会を補完する新作を発表します。 襲撃されたキブツの荒涼としたカフェや、粉々に砕かれ、不自然なポーズで吊るされた人形などの光景が、この悲劇を雄弁に物語っています。 これらの作品は痛みや悲しみの感情を呼び起こし、見る人の注意を引きつけ、共感や深い思索を促します。

素材や技術を試しながら、アーティストたちはあたかも歴史的遺物のような写真を作成します。 風化した紙の折り跡、不均一なエッジ、独特のグレースケールの色調は、時間の影響を伝えることを意図しています。 この視覚効果は見る者の印象を高め、神秘的で興味をそそるものであり、これらの写真が遠い昔、おそらく写真以前の時代に制作されたもの、あるいは私たちがそれらを遠い未来から見ているかのような錯覚を誘います。 作品は現代史の遺物となります。

All work was shot with Polaroid plates (positive/negative). The negatives are dried without pre-washing with traces of decomposed chemicals on them, then scanned, and then printed on rice paper. After printing, the work went through manual manipulation: aging the paper, folding, writing text…

作品は のポラロイドプレート(ポジ/ネガ)で撮影されました。ネガは予め洗浄せずに乾燥させ、その上に分解された化学物質の痕跡があります。次に、スキャンしてから、米紙に印刷されます。印刷後、作品は手作業での加工を経ています:紙の経年変化、折り目、テキストの書き込み等。

song by Swans “Screen Short”

Love, child, reach, rise, sight, blind, steal, light

Mind, scar, clear, fire, clean, right, pure, kind

Sun, come, sky, tar, mouth, sand, teeth, tongue

Cut, push, reach, inside, feed, breathe, touch, come

No pain, no death, no fear, no hate, no time, no now, no suffering

No touch, no loss, no hand, no sense, no wound, no waste, no lust, no fear

No mind, no greed, no suffering, no thought, no hurt, no hands to reach

No knife, no words, no lie, no cure, no need, no hate, no will, no speech

No dream, no sleep, no suffering

No pain, no now, no time, no here

No knife, no mind, no hand, no fear

Love! Now!

Breathe! Now!

Here! Now!

Here! Now!

Here! Now!

スワンズ の「スクリーンショット」という曲の歌詞

愛、子供、届く、上がる、視覚、盲目、盗む、光

心、傷、透明、火、きれい、正しく、純粋、親切

太陽、来て、空、タール、口、砂、歯、舌

切る、押す、届く、中に入る、食べる、息をする、触れる、来る

痛みも死も恐怖も憎しみも時間も今も苦しみもありません

触れない、失わない、手を持たない、感覚を持たない、傷を負わない、無駄を持たない、欲望を持たない、恐れを持たない

心も、貪欲も、苦しみも、考えも、傷も、届く手もない

ナイフも言葉も嘘も治療法も必要も憎しみも意志も発言もダメ

夢も睡眠も苦しみも無い

痛みはない、今はない、時間もない、ここにもいない

ナイフも心も手も恐怖も要らない

愛! 今!

息をする! 今!

ここ! 今!

ここ! 今!

ここ! 今!

Model: A reservist soldier of the Israeli army who participated in the Lebanon War (2006) and was wounded in it.

Contemplating on the subject of self-sacrifice: Young people (and not so young) give up everything, return from abroad at their own expense, and join the army at a time when the country is in danger, knowing and being aware of the unusually high risks of not returning. There is hardly another country in the world where you can observe this. We, who grew up in a culture based on Christianity (the literature of all Russian classics, the paintings of European museums…), could see parallels with the image of Christ, who also sacrificed himself for the sake of people. A quote from Holbein is used because, in our opinion, it is easiest to trace the parallel, and again, in our opinion, this is the most dramatic work with Christ after the descent from the cross (there are no additional characters, dynamics of poses, proportions of the work…).

Another reference is a poem by the Israeli-Russian poet Mikhail Gendelev. During the first Lebanese War, Gendelev was a military medic in the IDF; he was seriously wounded, the consequences of which haunted him for the rest of his life.

Mikhail Gendelev “Night maneuvers near Beit Jibrin” (Russian)

III

А нам читали: прорвались

они за Иордан

а сколько их а кто они

а кто же их видал?

огни горели на дымы

как должные сгорать

а мы – а несравненны мы

в искусстве умирать

в котором нам еще вчера

победа отдана

играй военная игра

игорная война

где мертвые встают а там

и ты встаешь сейчас

мы хорошо умрем потом

и в следующий раз!

III

And they were told: they broke through

Beyond the Jordan’s sand,

But who are they, and how many,

And who has seen this band?

Fires blazed into the smoke,

As they must blaze and burn,

But we, we are incomparable,

In art of death, we learn,

In which, just yesterday, was given

Victory’s own domain,

Play, the war game, gamble bold,

The gaming war, the bane,

Where dead arise, and there you stand,

And you stand now, in line,

We’ll die so well, another time,

In the next grand design!

(GPT translation)

モデル: レバノン戦争 (2006年) に参加し負傷したイスラエル軍の予備役兵士。

自己犠牲についての熟慮:若者(そう若くない人々も)は、国が危機に瀕している時に、すべてを捨て、自己負担で海外から帰国し、死ぬという非常に高いリスクを知りながら、軍に入隊します。世界の他のどの国でもこのようなことはほとんどありません。

キリスト教に基づく文化(ロシアの古典文学、ヨーロッパの美術館の絵画など)の中で育った私たちは、同じく人々のために自らを犠牲にしたキリストのイメージと類似を見ることができます。

キリストは人々のために自己犠牲を払いました。ホルバインの画像を引用するのは、類似点をたどるのが最も簡単だと私たちが考えるからです。私たちの意見では、これは十字架から下ろされた後のキリストを描いた最もドラマチックな作品です(余計な人物の追加や、ポーズのダイナミクス、作品のプロポーションなどがいっさいありません)。

別の参照先は、イスラエル系ロシア人である詩人ミハイル・ゲンデレフの詩です。最初のレバノン戦争中、ゲンデレフはイスラエル国防軍の軍医であり、重傷を負いました。その後の人生で彼は戦争で負った傷に苦しめられました。

この詩は、夢の中で家や家族を再訪し、世界が変わってしまったことに気づく兵士を描いています。彼は、死と戦争についての熟考とともに、妻と失った家庭の安らぎについて描写しています。 雪、月、蛾などの象徴的なイメージが詩全体に織り込まれており、生と死のさまざまな側面を表しています。詩の主人公は内なる葛藤に取り組み、悲劇と変容に彩られた世界における自分の役割を理解しようとしているように見えます。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, handwritten inscription with ink, 50 x 240 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、手書き、50 x 240 cm

Bush

Allegory to the “Message to Moses” in the form of a burning bush: “There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up. ” God called to him from the burning bush, urging him to lead the people of Israel from Egypt to the Promised Land.

“Not Dark Yet” by Bob Dylan

Shadows are falling and I’ve been here all day

It’s too hot to sleep, time is running away

Feel like my soul has turned into steel

I’ve still got the scars that the sun didn’t heal

There’s not even room enough to be anywhere

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there

Well, my sense of humanity has gone down the drain

Behind every beautiful thing there’s been some kind of pain

She wrote me a letter and she wrote it so kind

She put down in writing what was in her mind

I just don’t see why I should even care

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there

Well, I’ve been to London and I’ve been to gay Paree

I’ve followed the river and I got to the sea

I’ve been down on the bottom of a world full of lies

I ain’t looking for nothing in anyone’s eyes

Sometimes my burden seems more than I can bear

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there

I was born here and I’ll die here against my will

I know it looks like I’m moving, but I’m standing still

Every nerve in my body is so vacant and numb

I can’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from

Don’t even hear a murmur of a prayer

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there

In this song the phrase “It’s not dark yet” suggests that while things may not be great, there’s still hope and time for improvement. It implies that the speaker hasn’t reached a point of no return yet. If they can make positive changes, they can avoid spiritual decline or “darkness”.

“Train on Fire” by Russian band Aquarium

This train is on fire

And we have nothing left to reap

This train is on fire

And we have nowhere else to run

This land was ours

Until we get stuck in the fight

It will die if it belongs to no one

It’s time to take this land back

And torches are burning all around

All parts of the dead are being collected

And the people who shot our fathers

Making plans for our children

We were born to the sounds of marches

They scared us of prison

But stop crawling on your belly

We have already returned home

This train is on fire

And we have nothing left to reap

This train is on fire

And we have nowhere else to run

This land was ours

Until we get stuck in the fight

It will die if it belongs to no one

It’s time to take this land back

Этот поезд в огне

И нам не на что больше жать

Этот поезд в огне

И нам некуда больше бежать

Эта земля была нашей

Пока мы не увязли в борьбе

Она умрет, если будет ничьей

Пора вернуть эту землю себе

А кругом горят факелы

Это сбор всех погибших частей

И люди, стрелявшие в наших отцов

Строят планы на наших детей

Нас рожали под звуки маршей

Нас пугали тюрьмой

Но хватит ползать на брюхе —

Мы уже возвратились домой

Этот поезд в огне

И нам не на что больше жать

Этот поезд в огне

И нам некуда больше бежать

Эта земля была нашей

Пока мы не увязли в борьбе

Она умрет, если будет ничьей

Пора вернуть эту землю себе

“Train on Fire,” a song by Aquarium, was composed by Boris Grebenshchikov in Russian language and debuted in the late 1980s. Grebenshchikov has been influenced by Bob Dylan, but there isn’t a direct thematic connection between “Train on Fire” and Dylan’s “This Wheel’s on Fire.” Each song stands independently with its own distinct themes and lyrics.

The song addresses the theme of the necessity to put an end to conflicts and return to a peaceful life, to one’s home and land, which belong to the people rather than political or military groups. It serves as a call to halt violence and seek peaceful resolutions to conflicts.

ブッシュ

燃える芝の形をした“モーセへのメッセージ”のアレゴリー:

ときに主は、芝の中の炎の中に現れた。彼が見ると、芝が燃えているのに、その芝は、なくならなかった。神は燃える芝の中から彼に呼びかけ、イスラエルの民をエジプトから約束の地へ導くよう促しました。

ボブ・ディランの曲「まだ暗くない」

「まだ暗くない」作者: ボブ・ディラン

影が落ちている、俺はずっとここに居る。

眠るのに暑すぎて、時は過ぎて行く。

俺の魂が鋼に変わったような気分だ。

太陽では癒せない古傷が残る。

色んな所に行くのに部屋が足りない。

まだ暗くは無い、だけど近づいて来ている。

俺の人間性は排水口に流れて行った、

美しい物の全ての背後に、何かの痛みがある。

彼女は俺に手紙を、とても優しく書いた。

彼女の心の内を手紙に記した。

どうしてそんな物を気にしなきゃいけないのか分からない。

まだ暗くは無い、だけど近づいて来ている。

俺はロンドンに行ったし、パリにも行った。

川の流れを追いかけ、海に出た。

嘘で一杯の世界のどん底にも落ちた。

誰の目を見ても、何も求めていない。

時々、俺の重荷が耐えられる以上に感じる事がある。

まだ暗くは無い、だけど近づいて来ている。

俺はここで生まれて、予言に反してここで死ぬだろう。

俺が動いているように見えるのは分かる、だが俺はここで耐えて立っている。

俺の体にある全ての神経は、剥き出しになり、鈍っている。

俺が逃げ出すためにここに来させた物が何だったのかさえ思い出せない。

囁きや祈りさえも聞こえない。

まだ暗くは無い、だけど近づいて来ている。

(ブログ名久井翔太の音楽文章ラジオより翻訳)

この曲の「まだ暗くない」というフレーズは、状況は良くないかもしれないが、改善の余地と希望はまだあることを示唆しています。 これは、話者がまだ引き返せない地点に到達していないことを意味します。 前向きな変化を起こすことができれば、霊的な衰退や「暗闇」を避けることができます。

ロシアのバンドアクアリウムの曲「火事の列車」。

This train is on fire

And we have nothing left to reap

This train is on fire

And we have nowhere else to run

This land was ours

Until we get stuck in the fight

It will die if it belongs to no one

It’s time to take this land back

And torches are burning all around

All parts of the dead are being collected

And the people who shot our fathers

Making plans for our children

We were born to the sounds of marches

They scared us of prison

But stop crawling on your belly

We have already returned home

This train is on fire

And we have nothing left to reap

This train is on fire

And we have nowhere else to run

This land was ours

Until we get stuck in the fight

It will die if it belongs to no one

It’s time to take this land back

Этот поезд в огне

И нам не на что больше жать

Этот поезд в огне

И нам некуда больше бежать

Эта земля была нашей

Пока мы не увязли в борьбе

Она умрет, если будет ничьей

Пора вернуть эту землю себе

А кругом горят факелы

Это сбор всех погибших частей

И люди, стрелявшие в наших отцов

Строят планы на наших детей

Нас рожали под звуки маршей

Нас пугали тюрьмой

Но хватит ползать на брюхе —

Мы уже возвратились домой

Этот поезд в огне

И нам не на что больше жать

Этот поезд в огне

И нам некуда больше бежать

Эта земля была нашей

Пока мы не увязли в борьбе

Она умрет, если будет ничьей

Пора вернуть эту землю себе

アクアリウムの曲「火事の列車」はボリス・グレベンシコフがロシア語で作曲し、1980年代後半にデビューした。 グレベンシコフはボブ・ディランの影響を受けているが、「火事の列車」とディランの「This Wheel’s on Fire」の間にはテーマ上の直接的なつながりはない。 各曲は独自のテーマと歌詞を持って独立しています。

この曲は、紛争に終止符を打ち、政治団体や軍事団体ではなく国民のものである故郷や土地への平和な生活に戻る必要性をテーマにしています。 これは、暴力を停止し、紛争の平和的解決を求める呼びかけとして機能します。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, handwritten inscription with ink, 105 x 90 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、手書き、105 x 90 cm

Nails / Diptych

Nails from the Roman Empire period, approximately the beginning of the first century AD.

Shot on two Polaroid plates (positive/negative) measuring 3.25 x 4.25 inches. The negatives are scanned, printed on rice paper, torn into squares, and further manipulated with paints.

釘 / 二連作

紀元前1世紀初頭頃のローマ帝国時代の釘です。

2枚のポラロイドプレート(ポジ/ネガ)に撮影、サイズは3.25 x 4.25インチです。ネガはスキャンされ、米紙に印刷、四角に形を整え、さらに絵の具、コーヒー、紅茶で加工されます。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 70 x 170 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、 70 x 170 cm

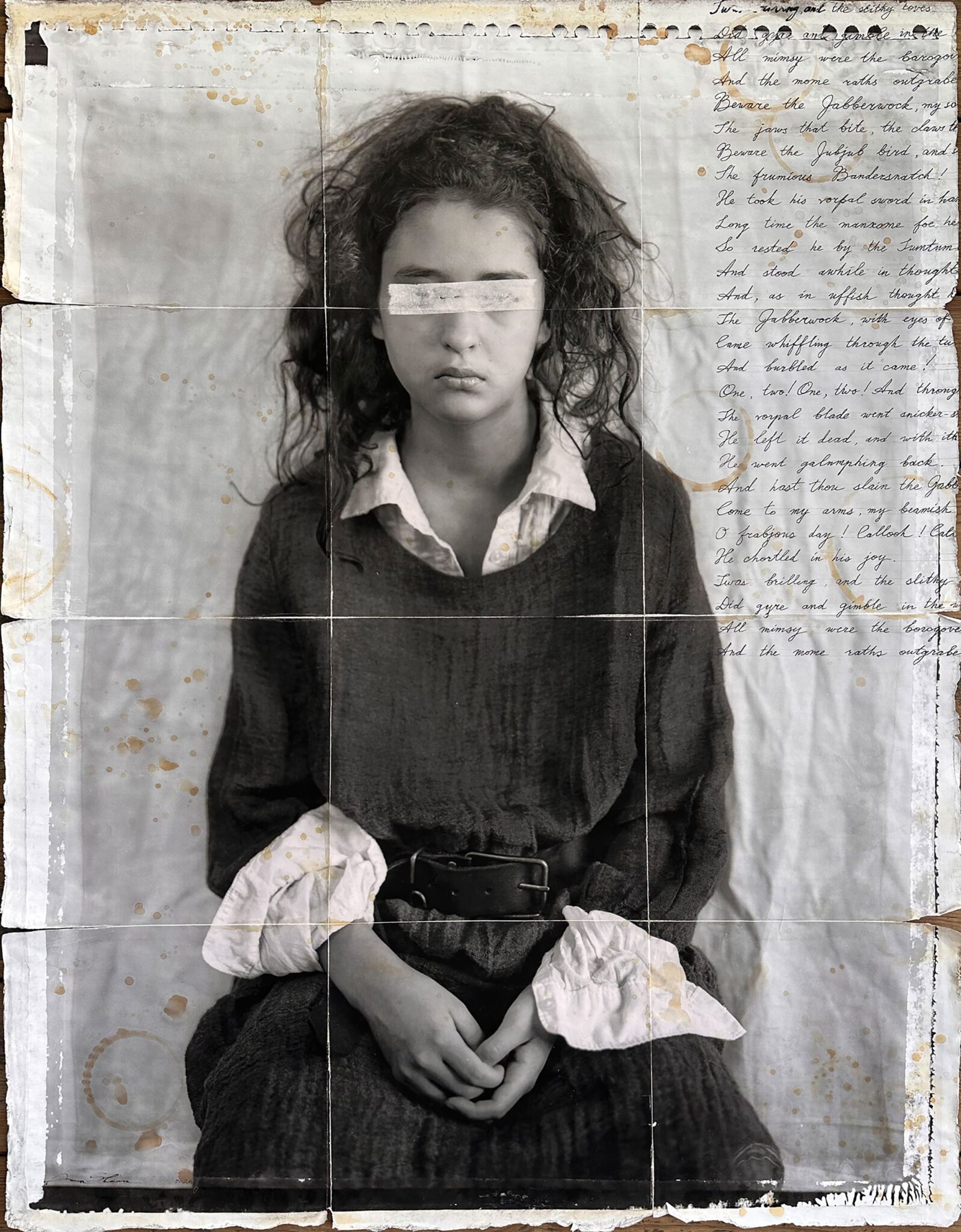

Ragged Coat

The model, is our daughter around 12 years old. She wears a World War II-era overcoat with a white soldier’s shirt.

Features the lyrics of Russian poet B. Okudzhava’s song “Ragged Coat” translated by Daniel Kahn

I wore my ragged coat so bare

The tattered sleeves were thin as paper

And so I took it to a tailor

And asked him kindly for repair

I made a joke, and said

“This coat requires total restoration

To bring me glory and salvation

I need your skillful hands to sew!”

But then my playful little words

Took on a meaning unintended

As he methodically mended

He seemed disturbed

Peculiar bird…

And I observed the silent way he worked

To rectify the garment

As though my soul depended on it

This ragged coat, for all my days

He thought I’d slip into the sleeve

And I’d believe again so clearly

That somehow you could love sincerely

But that’s absurd

Peculiar bird…

This song is about a man who metaphorically views his life, imagining it as a long-worn jacket he wears. He calls a tailor to remake this jacket so that it looks new and successful again. Through humorous words, he expresses hope for a change in his life. At the same time, the tailor, taking his work seriously, tries to create something special that will make his client happy. The song also contains some irony and self-irony when it talks about how the tailor imagines that changing the jacket will lead to a change in the person’s feelings.

ぼろぼろのコート

モデルは、およそ12歳のときの私たちの娘で、第二次世界大戦時代のオーバーコートを着用し、白い兵士のシャツを着ています。

ソ連・ロシアの詩人ブラート・オクジャヴァの歌 「ぼろぼろのコート」(Ragged Coat)の歌詞、ダニエル・カーン訳

I wore my ragged coat so bare

The tattered sleeves were thin as paper

And so I took it to a tailor

And asked him kindly for repair

I made a joke, and said

“This coat requires total restoration

To bring me glory and salvation

I need your skillful hands to sew!”

But then my playful little words

Took on a meaning unintended

As he methodically mended

He seemed disturbed

Peculiar bird…

And I observed the silent way he worked

To rectify the garment

As though my soul depended on it

This ragged coat, for all my days

He thought I’d slip into the sleeve

And I’d believe again so clearly

That somehow you could love sincerely

But that’s absurd

Peculiar bird…

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, handwritten inscription with ink, 104 x 82 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、手書き、104 x 82 cm

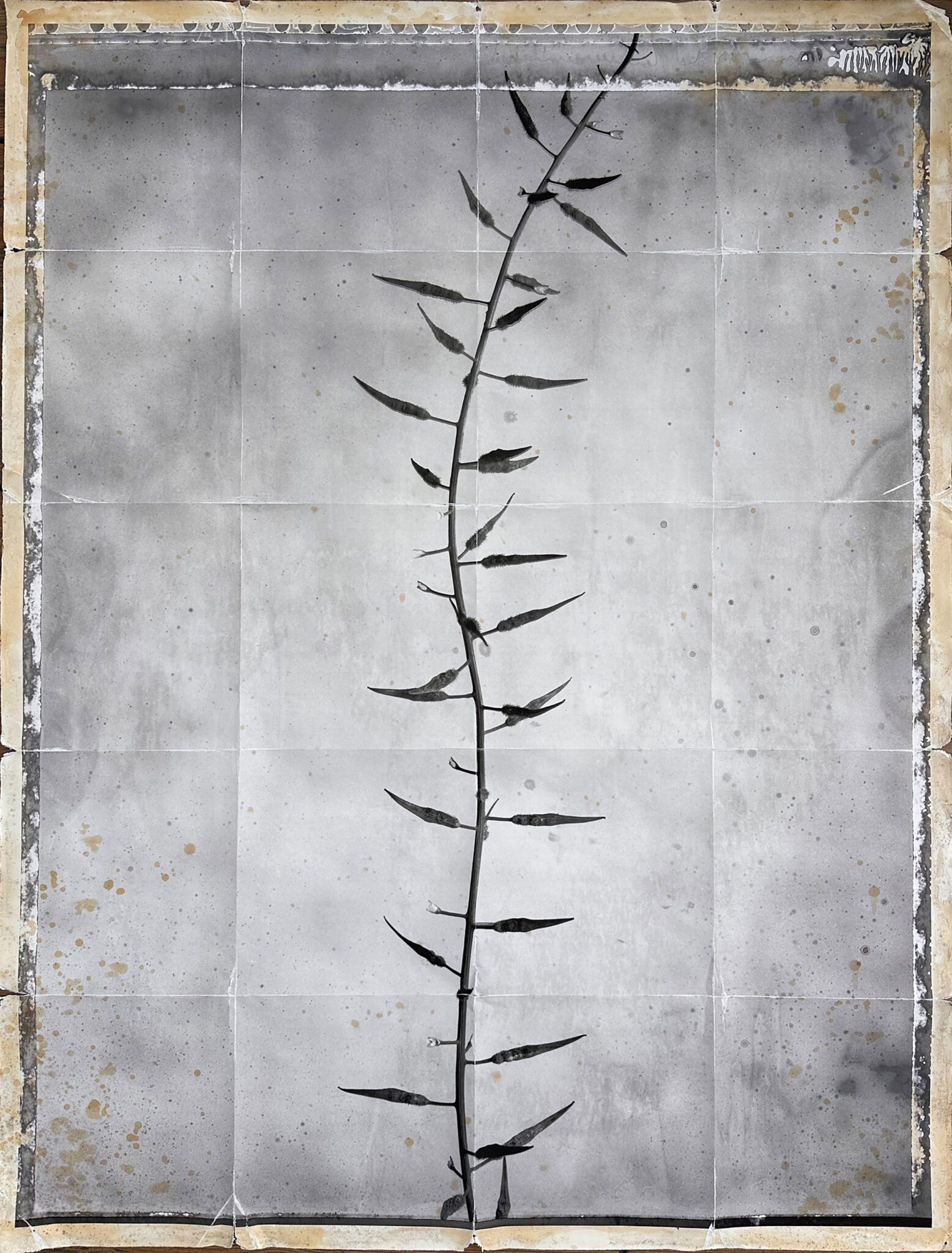

Scar (Wild Mustard)

This plant thrives in the harshest conditions. Fields of wild mustard blanket the ground in late winter, their vibrant yellow flowers transforming into dense thickets of dead wood by midsummer. Serving as an allegory of rebirth and cyclicality, it symbolizes vitality and protection, acting as a natural defense against pests and predators.

傷跡 (ワイルドマスタード)

この植物は、最も過酷な条件下でも繁栄します。

冬の終わりには、野生のマスタードの野原が地面を覆い、その鮮やかな黄色の花が夏の半ばには密な枯れ木の茂みに変わります。

再生と周期性の寓意であることを示唆し、生命力と保護を象徴し、害虫や捕食者に対する自然の防御として機能する植物もなっている。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 103 x 79 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、103 x 79 cm

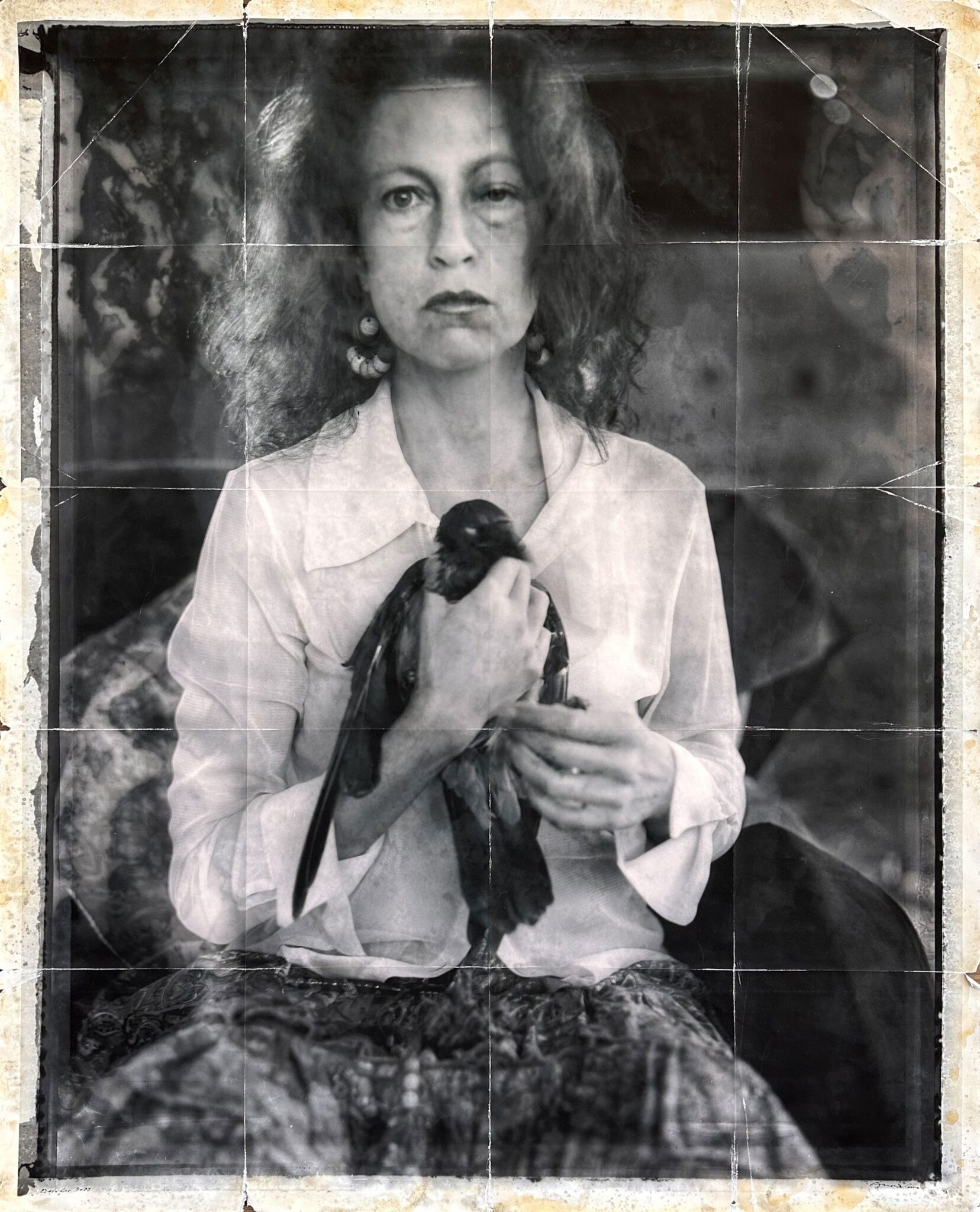

Lady with a Wounded Raven

負傷したカラスを抱く貴婦人

この画像では、黒い目と負傷したカラスを特徴として、マドンナと鳩の優美で軽やかな描写とは対照的です。それは慈悲と思いやりのテーマのアレゴリー(寓意)として機能し、同時に抵抗と闘いを象徴しています。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 104 x 84 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、104 x 84 cm

Tel Aviv Under Fire

Lyrics by Pink Floyd, album The Wall “Goodbye Blue Sky”

Did you see the frightened ones?

Did you hear the falling bombs?

Did you ever wonder why we had to run for shelter when the

Promise of a brave new world unfurled beneath a clear blue sky?

テルアビブが砲火を浴びる

ピンク・フロイドのアルバム 「ザ・ウォール」(The Wall)の歌詞、「さようなら、青い空」(Goodbye Blue Sky)

おびえた人たちを見ましたか?

落ちてくる爆弾の音を聞きましたか?

不思議に思いましたか?

何故私たちはシェルターに駆け込まなくてはならなかったのでしょう

勇気な新しい世界という約束が翻されたときに

まっさらな青い空の下で。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, handwritten inscription with ink, 80 x 100 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、手書き、80 x 100 cm

Dandelion

Dandelion as an allegory of paratroopers.

A reference to the poem “September 1982” by the Israeli-Russian poet Mikhail Gendelev.

This poem reflects on the indifference of the Lord towards earthly matters, portraying a scene where nature and war coexist in a strange harmony. The first stanza describes the slow unfolding of nature amidst the smoke of war, with tanks moving methodically towards their destination, likened to a prayerful procession. The second stanza continues this theme, suggesting that even the simplest elements of nature, like dandelions in the wind, yearn for a higher realm. The final stanza addresses the Lord directly, questioning what dreams or visions occupy His mind while the poet fills pages with thoughts of love and immortality, contrasting with themes of destruction and death. The mention of a black and crimson butterfly symbolizes the readiness to transcend earthly confines.

タンポポ

ロシア系イスラエル人の詩人ミハイル・ゲンデレフの詩への言及 (「1982年9月」)

この詩は、地上の問題に対する主の無関心を反映しており、自然と戦争が奇妙な調和の中で共存している情景を描いています。 最初のスタンザは、戦争の煙の中でゆっくりと展開する自然を描写しており、戦車が目的地に向かって整然と移動しており、祈りの行列に例えられています。2番目のスタンザもこのテーマを継続しており、風になびくタンポポのような自然の最も単純な要素でさえ、より高い領域を切望していることを示唆しています。 最後の節は主に直接語りかけ、主の心を占める夢や幻が何であるかを問う一方、詩人は破壊と死のテーマと対照的に、愛と不死についての考えでページを埋め尽くします。 黒と深紅の蝶についての言及は、地上の限界を超越する準備ができていることを象徴しています。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 104 x 84 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、104 x 84 cm

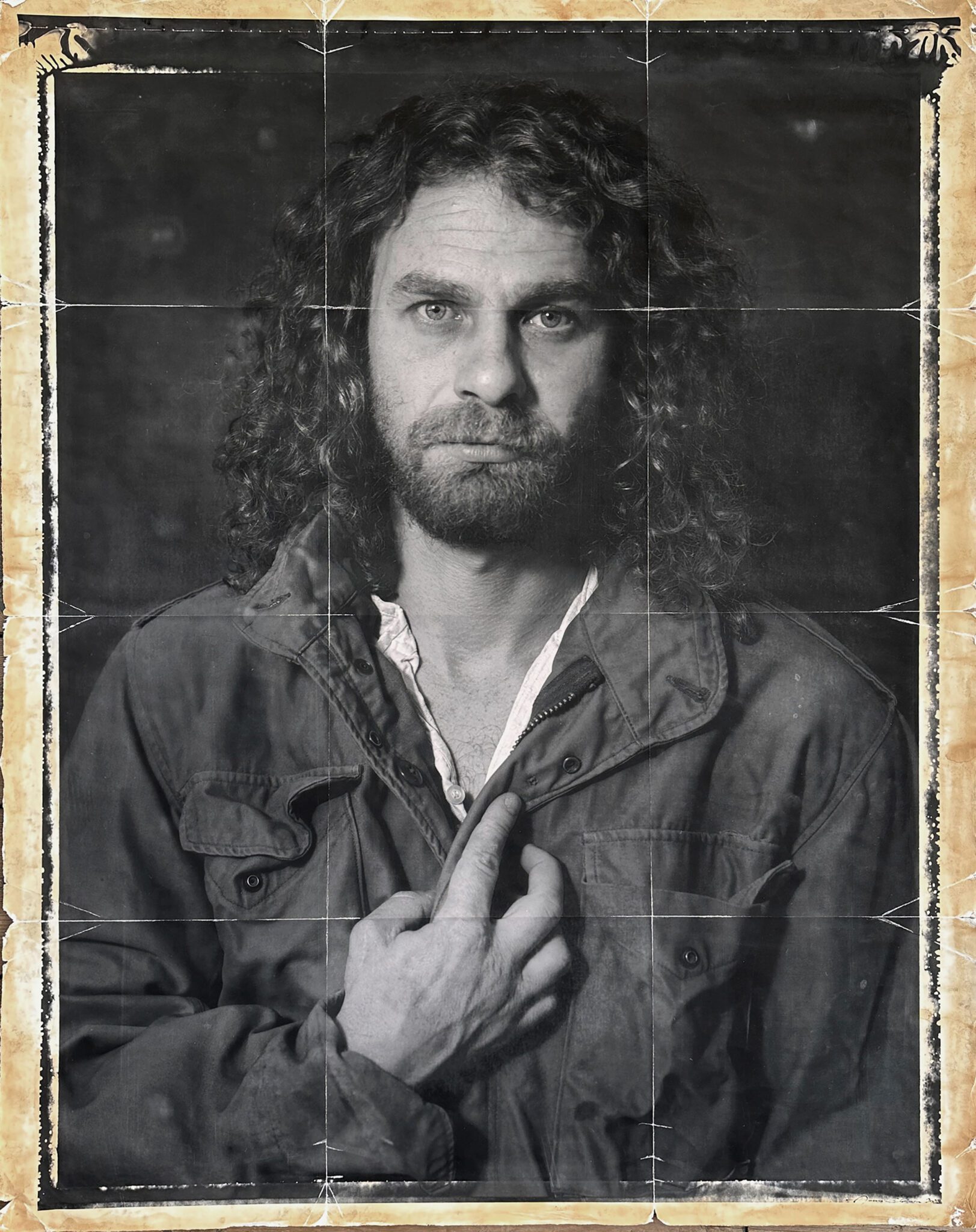

After Dürer

A portrait of an Israeli soldier who experienced the Lebanon War 2006 is a continuation our discussions about self-sacrifice and references to the image of Christ.

Why After Dürer?

Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait from 1500 is strikingly reminiscent of the iconic imagery seen in earlier depictions of Christ. Dürer intentionally adopted the same composition used by medieval artists for portraying Jesus. To him, this choice held a profound significance: it symbolized that a person should not only physically resemble the Savior but also embody a deeper, metaphorical likeness by embracing and enduring the challenges of life, akin to carrying the symbolic “cross.”

Inspired by Dürer’s approach, we directly incorporate the iconography of his self-portrait into a contemporary photographic portrayal of a soldier. The central theme of this artwork is the recognition that the essence of Jesus can be found within everyone.

デューラーの後

2006 年のレバノン戦争を経験したイスラエル兵士の肖像画は、自己犠牲とキリストの像への言及についての議論の続きです。

なぜデューラーの後に?

1500 年のアルブレヒトデューラーの自画像は、以前のキリストの描写に見られた象徴的なイメージに倣っています。デューラーは、中世の芸術家がイエスを描くために使用したのと同じ図像を採用しました。

彼にとって、この選択は深い意味を持っていました。デューラーが芸術家としてのみならず、個人としても、「キリストに倣って生きよう、その苦難を自らも負い、耐え忍ぼうという宗教的信念を持っていたことが示されています。

デューラーに倣い、私たちは彼の自画像の図像を直接使用して、兵士の写真ポートレートで現代世代を描きます。 この作品の主なメッセージは、あらゆる人の中にイエスを見ることができるということです。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 104 x 83 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、104 x 83 cm

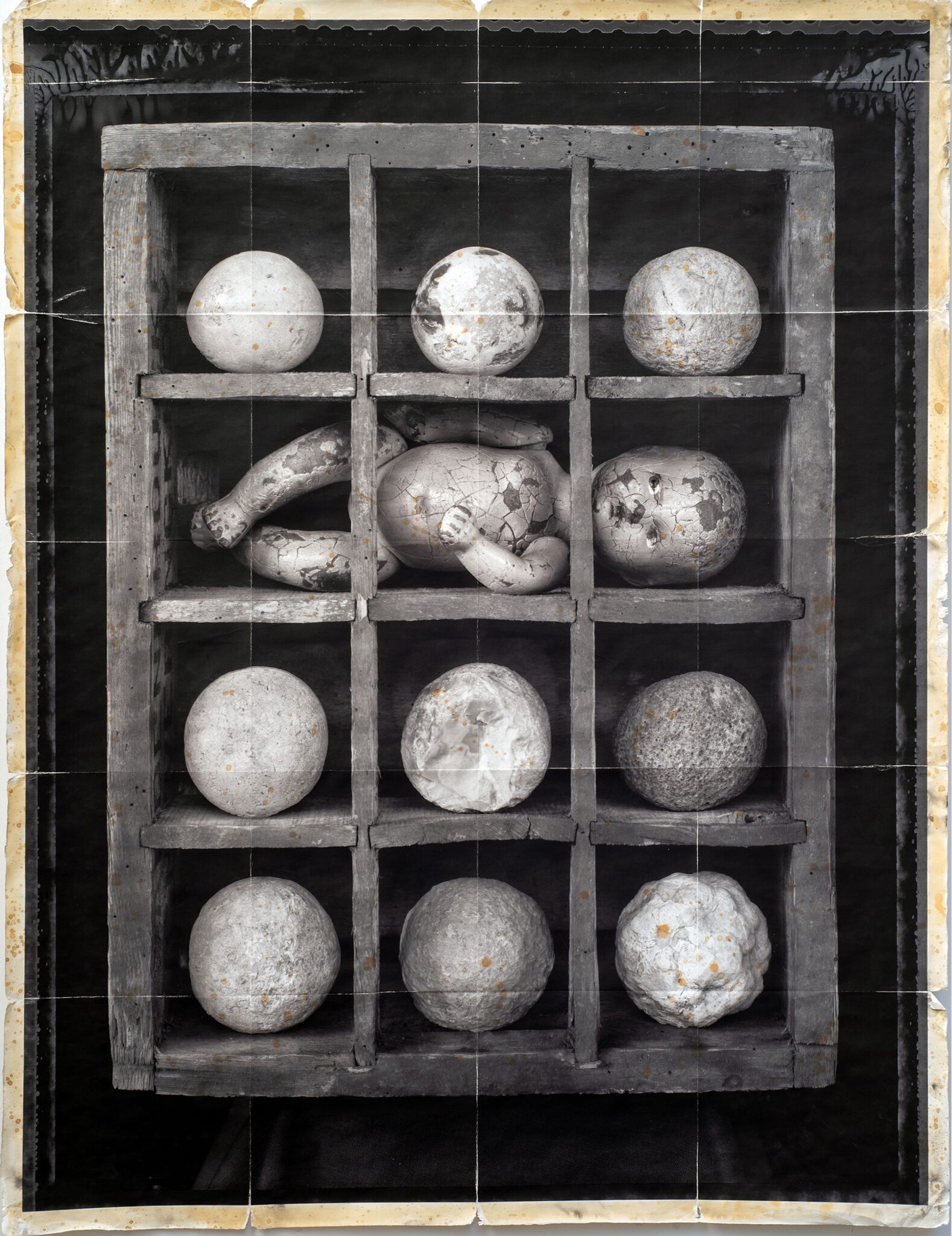

Doll in a Milk Bottle Crate

Milk Bottle Crate – Symbolizing freedom of choice.

Reference to Sholem Aleichem’s ‘Tevye the Dairyman”

“Tevye the Dairyman” by Sholem Aleichem is about the life and struggles of Tevye, a Jewish dairyman living in the fictional village of Anatevka in Tsarist Russia. The story follows Tevye as he grapples with various challenges, including poverty, anti-Semitism, and the changing social dynamics within his community. Through Tevye’s humorous and poignant narratives, the novel explores themes of tradition, family, faith, and the clash between old ways and modernity.

In “Tevye the Dairyman” by Sholem Aleichem, the theme of choice revolves around the protagonist Tevye’s decisions and their consequences within the context of changing social and economic conditions. Tevye, a Jewish dairyman in Tsarist Russia, grapples with various choices related to his family, tradition, and faith as he navigates the challenges of a rapidly evolving world. His decisions regarding arranged marriages, religious observance, and interactions with the broader society reflect his attempts to balance tradition with modernity. Ultimately, the theme of choice underscores Tevye’s struggle to maintain his cultural identity and moral integrity amidst societal changes.

An old doll with cracked paint – a reference to a wounded childhood.

The stones represent a Jewish custom to put stones on graves. There are different interpretations, for example meaning enduring memory. Unlike flowers, which wilt and fade quickly, stones endure, symbolizing the timeless presence of the departed in our hearts.

The overall sentiment behind our work reflects the atrocities inflicted upon Israeli children by terrorists on October 7th.

人形

ミルク瓶の木箱 – 選択の自由を象徴しています。

ショーレム・アレイヘムの「牛乳屋テヴィエ」への言及

ショレム・アレイヘムの「牛乳屋テヴィエ」は、帝政ロシアの架空の村アナテフカに住むユダヤ人の酪農家テヴィエの生涯と闘争を描いた作品です。 物語は、貧困、反ユダヤ主義、コミュニティ内の社会力学の変化など、さまざまな課題に取り組むテヴィエを追っています。 テヴィエのユーモアと感動に満ちた物語を通して、この小説は伝統、家族、信仰、そして古いやり方と現代性の衝突といったテーマを探求しています。

ショレム・アレイヘムの「牛乳屋テヴィエ」では、変化する社会的および経済的状況の中での主人公テヴィエの決断とその結果を中心にテーマが選択されています。 帝政ロシアのユダヤ人の酪農家であるテヴィエは、急速に進化する世界の課題を乗り越えながら、家族、伝統、信仰に関するさまざまな選択に取り組んでいます。 見合い結婚、宗教的遵守、より広範な社会との交流に関する彼の決断は、伝統と現代性のバランスをとろうとする彼の試みを反映しています。 結局のところ、選択したテーマは、社会の変化の中で自分の文化的アイデンティティと道徳的完全性を維持しようとするテヴィエの苦闘を強調しています。

ひび割れた塗装の古い人形 – 傷だらけの子供時代への言及。

石は墓に石を置くというユダヤ教の習慣を表現します。さまざまな解釈があります。たとえば、永続的な記憶を意味します。花がすぐにしおれて消えるのに対して、石は持続します。それは、亡くなった人々が私たちの心に永遠に存在していることを象徴しています。

私たちの作品の背後にある全体的な感情は、10月7日にテロリストによってイスラエルの子供たちに加えられた残虐行為を反映しています。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 105 x 84 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、105 x84 cm

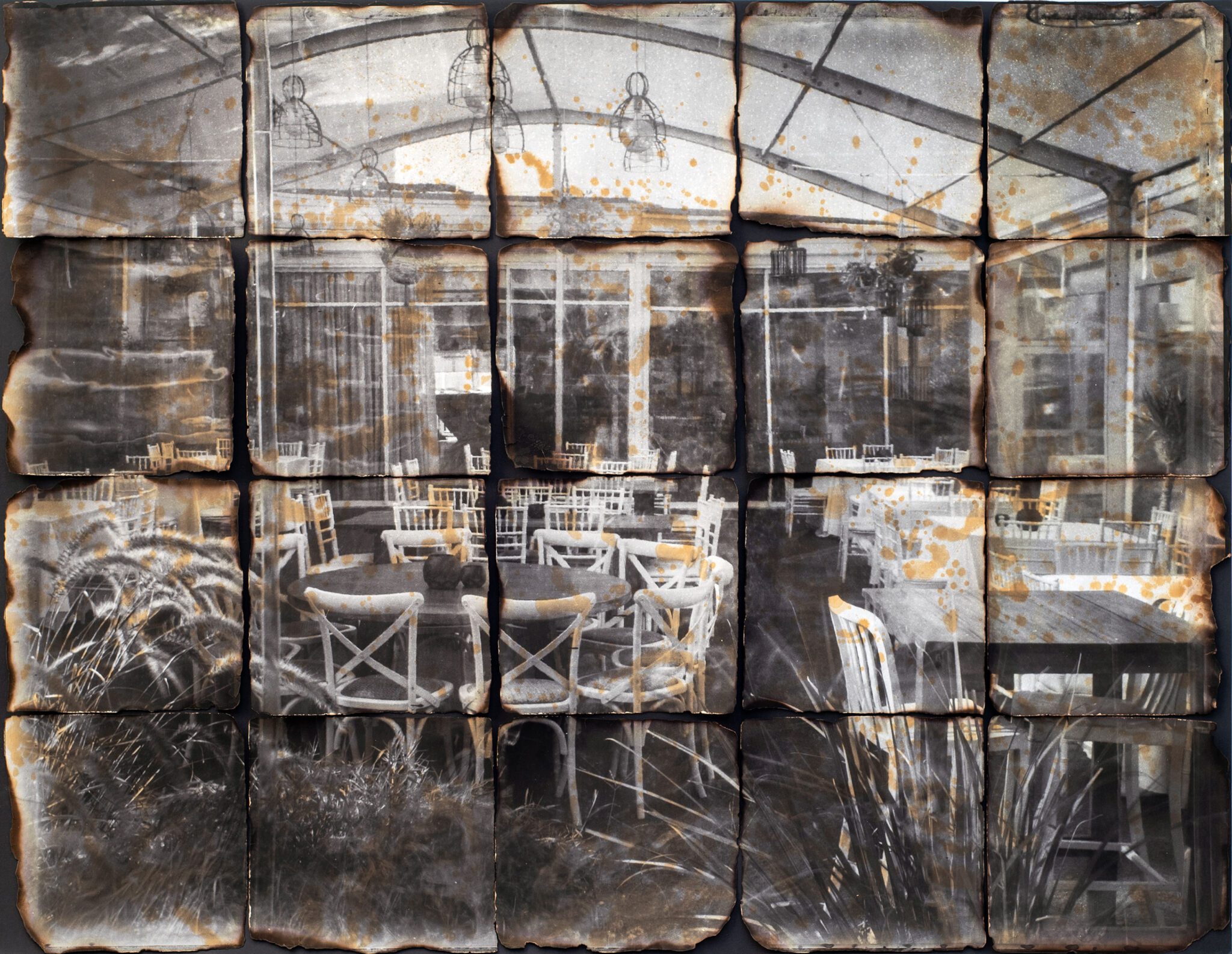

Abandoned Cafe (Be’eri)

After the events of October 7, a video from the scene depicted the charred remains of a dining room wall at Kibbutz Be’eri. On it, there was a notice board adorned with notices and photographs that were nearly completely burnt. This served as the inspiration for the creation of this work.

A reference to the dining room in the kibbutz*, a place where people gathered and united for shared meals, intertwines with a reference of the Last Supper of Jesus.

The burnt remnants of a photograph represent lives, quite literally burnt away.

It is important to note that since the edges of the artwork were burned, its deterioration over time due to fire damage is inherent to the concept.

*A kibbutz is an agricultural commune in Israel, characterized by communal property and equitable distribution of labor and resources.

人形

10月7日の出来事の後、現場からのビデオの1つが、キブツ・ベエリの焼けたダイニングルームの壁を示していました。壁には、ほとんど完全に焼けた掲示物、写真などがある掲示板がありました。ここれがこの作品を作成するきっかけとなりました。

キブツ*の食堂、つまり人々が集まり、食事を共にする場所への言及が、イエスの最後の晩餐への言及と絡み合っています。写真の焼け跡は、文字通り焼き尽くされた人生を表しています。

作品は火災の影響で時間の経過とともに劣化していくことが重要です。そして、その破壊の過程はこの作品の概念の一部です。

*キブツは、イスラエルにある農業共同体であり、共同財産と労働・資源の公平な分配を特徴とします。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, fire, 70 x 91 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、70 x 91 cm

Esther

This piece references the biblical figure of Esther, known for her courage and devotion to her people. Esther, originally a relative and later adopted daughter of the Jew Mordecai, resided in Susa during the reign of the Persian king Artaxerxes. She played a crucial role in saving the Jewish population from destruction.

Esther’s rise to prominence stirred envy and anger among some courtiers, notably Haman, an Amalekite official known for his arrogance and despotic rule. Upon learning of Haman’s plot to exterminate the Jews, Mordecai urged Esther to intervene. Despite the risks, Esther boldly approached the king, defying court etiquette, and pleaded for her people’s safety. The king, moved by her plea, ordered Haman’s execution and revoked the decree of Jewish extermination.

The tomb of Esther and Mordecai, along with a temple dedicated to them, is located in Hamadan, Iran.

Additionally, we would like to make a reference to Esther Hayut, former President of the Supreme Court of Israel. She became a symbol of safeguarding justice in the conflict between the government and civil society, particularly amidst the government’s attempts to control the judiciary.

Lewis Carroll “The Jabberwocky”

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Jabberwocky” is a nonsense poem written by Lewis Carroll about the killing of a creature named “the Jabberwocky”. It was included in his 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The book tells of Alice’s adventures within the back-to-front world of the Looking-Glass world. “Jabberwocky” is considered one of the greatest nonsense poems written in English. Its playful, whimsical language has given English nonsense words and neologisms.

This text is written in the form of a scroll (megillah). It is a scroll similar to the “Scroll of Esther” and “Israel’s Declaration of Independence” called the Megillah Ha’tzmaut. The Scroll of Independence is a legal document that declares the formation of the State of Israel and sets out the basic principles of its organization.

ぼろぼろのコート

モデルは、およそ12歳のときの私たちの娘で、第二次世界大戦時代のオーバーコートを着用し、白い兵士のシャツを着ています。

ルイス・キャロル『ジャバウォックの詩』

Polaroid photograph, aged rice paper, handwritten inscription with ink, 104 x 82 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、手書き、103 x 80 cm

Baby dolls

The baby doll, in an association with childhood and innocence, symbolizes playfulness, joy and carefree moments. However, on October 7 childhood and joy were shattered, leaving behind only stones.

Stones can symbolize a connection to the departed and serve as a lasting reminder that memories of the dead endure eternally, akin to the resilience of stone against the passage of time. Additionally, they reference the biblical tale of David and Goliath, representing protection and defense.

ベビードール

ベビードールは幼少と無邪気さを連想させ、遊び心、喜び、気楽な瞬間を象徴しています。しかし、10月7日、幼少と喜びは打ち砕かれ、石だけが残されました。

亡くなった人とのつながりの象徴としての石は、時間に耐える石そのものと同じように、死者の記憶が永遠に続くことを思い出させてくれます。さらに、保護と防御を表す聖書のダビデとゴリアテの物語も参照しています。

Polaroid photo, aged rice paper, 104 x 84 cm

ポラロイド写真、ライスペーパー、手書き、104 x 84 cm