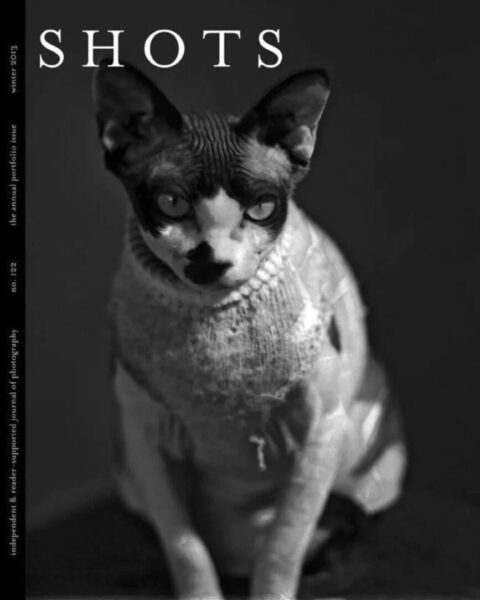

– featured and interviewed in SHOTS no. 122

No. 122 – Winter 2013

Theme: Annual Portfolio Issue

Cover: Anna Hayat & Slava Pirsky

Interviews: Allan Barnes, Alicja Brodowicz, Anna Hayat & Slava Pirsky, Richard C. Johnson, Rene Koster, Julie Meridian, Cade Overton, Agaschinka Schmunst, and Michael Wilson

More information at www.shotsmag.com

Order at www.shotsmag.com/orders.htm

Interview with Anna in SHOTS #12:

How did you come to know each other, and what led to the decision of you collaborating together?

I was a second-year photography student at Hadassah College, and a friend of mine was studying in the Film Department and was shooting her thesis film. Slava and I met while making the sets for this film. He began to drop by the college, where I was living, basically. We would drink wine, discuss life, art, photography, and that’s kind of how it started… Then, our daughter was born, and there was nothing for us to do but to start on a collaborative project to document the milestones of her childhood.

Tell me more about your collaboration and how you work together. Do you take on specific roles in your process? Do you feel that you compensate for each other’s strengths and weaknesses as photographers or otherwise?

First, one of us has a thought or even a frame appear in the mind. Then we discuss it for a fairly long time, make sketches; sometimes we even shoot using materials less complex or expensive than Polaroid (Pola has practically disappeared from stores, and those stocks that still exist are long past their expiration date, so we have to be very careful with how much film we use). Once the idea and the sketches are good enough for both of us, we shoot using Polaroid. And here’s where yet another element comes into play. Shooting with a studio camera, you end up putting in the film cartridge last, which is why you finish working on the shot almost blind. And because of the fairly long exposure, it’s possible that the person (if it’s a person we’re shooting) who is by this time pretty exhausted by the set-up of the shot, has moved slightly or shifted his gaze. What happens is that the camera’s unpredictability factor comes into play. Plus, the Polaroid itself makes its own contributions to the shot; the closer we are to its total disappearance from this world, the greater the metamorphoses happening with the material. In the end, you don’t know either way what, if anything, will develop. There’s definitely a mystical moment in all of this, which is why we love it; and the studio camera, too. I guess these things compensate for our perfectionism in the set-up of the shot.

With the two of us working together, it makes absolutely no difference who ends up pressing the shutter button. Usually it’s the one closest to the camera at the moment, or the one whose hands are free.

Do we counterbalance each other? I’d say complement is a better word. For me, photography has always been an attempt to express my thoughts on life, a search for answers to certain questions. For Slava, photography means the creation of an ideal shot, the search for absolute beauty.

What led to the decision to shoot large-format and Polaroid? How do you feel your process best conveys what you want to communicate with your photography?

As I’d already mentioned, it’s the final shot’s unpredictability, plus the fact that a large-format camera naturally predisposes one to work without hurrying. It demands maximum concentration on the process – from both us and the subject. We ask our models to make at least three or four hours available for shooting. In today’s hyper-fast world this ends up being akin to a meditation. In contrast to what’s usually thought of as the essence and aim of photography, we don’t strive to capture a moment snatched from the flow of reality; we actually look for the flip side of that moment, shooting that which could have been but didn’t happen because we live our lives too fast. Or maybe it happened, but no one noticed it because everyone had run off ahead. Today’s technology has accelerated reality past the bounds of the impossible; just try to get someone and freeze them for a second, or maybe even two seconds – they’ll collapse in on themselves. As a result, in the shot we see a person totally different from the one who was sitting in front of the camera at that moment.

What is typically your process when editing? Do you think of your work as having a sequence or larger narrative?

For our latest project, which we’re working on now, as early as the discussion and sketch stage we started putting it together like a big story. Although we most often shoot separate frames that are self-contained stories. They’re collected into big stories later on one way or another, like a collection of short stories with a single title. And here is where the advice of a good curator comes very handy, since we’re so deeply enmeshed in our work that it’s hard to have an outside perspective on the project, and to rid it of everything that doesn’t belong.

Tell me about where you live. How do you feel it most influences your work?

We live on the outskirts of Jerusalem. We found the coldest part of the country and stayed here; I was born above the Arctic Circle and, even after 15 years in Israel, the summers here are still too hot for me. This country is very vivid, very boisterous, with too much light and noise, everything in contrast to everything else, everything showing itself off. Plus, the City is just too old, too heavy, like a spider sitting at the center of a web overfilled with captive souls. And you want to hide from all of these things, you want to dim the lights, turn down the volume… I don’t know… I think the City comes through in our photographs all the same. Although our mutual obsession with the Northern Renaissance comes through more, if only because we quote it so often in our work.

Do you keep a journals or sketchbooks? If so, what form do they take?

Not notebooks as such, but we do have separate sheets of paper with sketches, books on art with pages marked, all sorts of notes with thoughts, also proof prints. Everything lies in a pile so it can be mixed up and rearranged to help us look for the possibilities in creating a project or for ideas on how to keep something going.

In summary, what does your work most mean and bring to your lives?

Our photography probably has the greatest effect on our daughter. We try to shoot her once a week. She knows for sure that she’ll never be a model or a film actress, and is waiting for the day she turns 18 when we finally finish the project she’s the star of. But, seriously, our lives always revolve around the project at hand. We’ve long ago been looking at the world around us through the lens of an imaginary camera: we construct shots in our heads of places we like, we look at each new acquaintance as a potential model, we read a lot of books on philosophy, and go to look at old and modern art. In today’s world, doing analog photography is a luxury, and you have to just work a lot to be able to grant yourself the opportunity to do what you love.